Maps of the known and unknown in Daydreaming on the Porch

- June 25, 2020, 3:01 a.m.

- |

- Public

My fascination with maps goes back a very long time. In fact, I can trace the exact year — it was 1959, and we lived in a suburb of New Orleans in a small two-bedroom apartment. I was nine years old, and that year the World Book Encyclopedia came into my life. I was drawn in immediately to this amazing repository of information and pictures, articles, facts, statistics and best of all, maps.

I’ve always been interested in books and had a healthy curiosity going back to my early childhood. I remember the Golden Books series and being fascinated by the seemingly endless subjects and stories. But then that set of encyclopedias appeared, and my inquisitiveness and curiosity seemed to take off. It seemed to awaken me, and I was suddenly no longer a child. I’m not sure what age a child begins to have that awareness, but I think I was starting to because the more I read in the encyclopedia, the more curious and interested I became in learning and school.

I pored over volumes of the encyclopedia and remember being quite curious to learn about the countries of the world. I honed in on the maps to find the capitals and largest cities. I was always interested in the populations of cities, large and small, all around the world and in the U.S. Fascinating too, were the maps of rivers and ports where the major rivers met the sea. To this day the texture and color of those encyclopedia volumes are ingrained in my memory. Even when I found sets of old encyclopedias such as Compton’s and Funk and Wagnals in used bookstores years later, I’d immediately be drawn to the maps in those old encyclopedias.

Later in the 60s when I was 12 or 13, I remember for the first time getting really absorbed in road maps, as twice a year at Christmas and in the summer my parents, brother and sister, and I, would jam into our sturdy stick-shift Chevy Bel-Air, and later an Olds 88, and make the 750-mile trip from New Orleans to South Carolina with my father at the wheel barreling down the old US highways that preceded the Interstates. He’d drive straight through and we’d usually get there about 11 at night, exhausted from the long trip but so excited to see my aunt and grandparents. These trips during the 60s were a big deal for me, as I yearned to leave the big city and see the rural countryside and small towns in Alabama and Georgia on the way. I couldn’t wait to get to the first filling station, stretch and get a bottle of Coke and some Lance crackers and then get my hands on one of the free, folding Gulf or Esso road maps. Next to the counter in the gas station there was always a rack with road maps, sometimes with maps of several states, or two in one map, or a map of the Southeastern US. I liked to get the larger, single-state maps because there was so much more detail. I’d get back in the car, open up the rather large map, and start tracing our route. It was fascinating to imagine what all the little towns we passed though were like, what their populations were, and the distances between towns. This was important because once we were in Georgia and well past the halfway mark, our excitement about getting to our destination would mount, along with the level of our fidgetedyness. We passed through so many little towns, all with interesting main streets. I think I used to try to count the number of dime stores we passed. I was really drawn to those small towns, different from where I lived. I wondered what it would be like to live in such a town. In my early and mid-teens, I r didn’t like living in New Orleans that much. Thus on vacations, I would idealize small towns for their perceived old fashioned virtues and innocence compared to the big cities. Little did I know, as I later discovered. This was also before I had read Sinclair Lewis’ classic novel about small towns, “Main Street.” It was also before I served as editor several small town weekly newspapers. No map could have guided me through the mazes I found myself in.

We’d drive another 15-20 miles and come to another town, sometimes larger little cities. Those road maps were something I could always count on to occupy my time during long drives in the car. As an adult, when I actually took my own car trips around the country, maps naturally were essential in planning those wonderful travel odysseys. I was so full of anticipation and excitement about seeing places I’d never seen before. I bought books that gave detailed maps of certain parts of each state where there were interesting historical attractions, natural features in the landscape that were unusual or particularly significant, or state and national parks that were often less visited little jewels of discovery. The detailed maps in books would take me on the fabled “blue highways” that William Least Heat Moon wrote about so memorably in his first book of that title published in 1982.

According to an entry in Wikipedia, He had coined the term to refer to small, forgotten, out-of-the-way roads connecting rural America (which were drawn in blue on the old style Rand McNally road atlas).

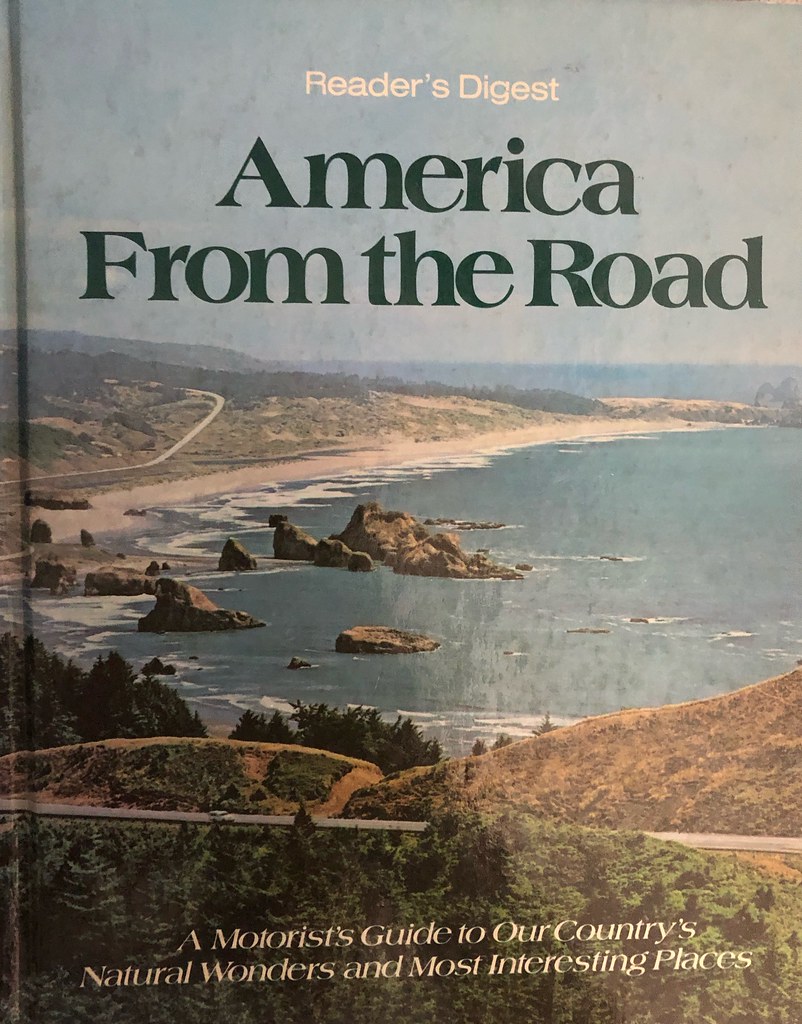

“America From the Road” was my first and best ever go-to guide as I planned that first round-the-country trip. Each state had amazing maps of sections of the state, featuring usually circular back road mini-trips with numbered sites and places to visit along the way. I ended up taking that book’s advice almost exclusively, and it paid off. I would use those in addition to the Mobil Travel Guides which I used to find places to stay for the night. My main travel maps were in the yearly, updated Rand McNally Road Atlases, which we’re indispensable. I would buy this huge atlas every year before beginning my 6-7,000 mile road trips. They never failed me. After one of those trips, the Atlas pages would be so worn and tattered they’d practically be falling out. Many nights at motels would find me propped up on the bed going over all my books and maps. The thrill was was the adventure into the unknown. “What will I see and experience tomorrow?” “Where will those “blue highways” take me? I or quite good at reading maps.

In addition, whenever I could, I would stop at National Forest Service offices and get maps of thenational forests I would be traveling through. They had the minutest details of dirt and gravel roads, streams and rivers, and even the locations of small springs. I could pinpoint waterfalls and picnic sites. These maps were overwhelming in their abundance and richness of detail. The only maps with more detail were topographic maps. Looking closely at those Forest Service maps, either before or after I’d been diving all day, was a delightful exercise of the imagination because you knew you’d never get to see all the places in there, but just knowing they were there made it that much more fun. I would often say, “That’s a place I want to see next time.”

The only drawback to looking at Forest Service and topographic maps was that I could only dream about seeing most of those places. But they got me thinking about what endless travel like would be like in retirement if I had some sort of small Van RV. But that’s another whole realm of contemplation. I recommend the magazine “Rova” for that.

I remember in a North Carolina mountain town finding a store devoted to nothing but maps. I could hardly believe my luck. I had never seen a place like that before or since.

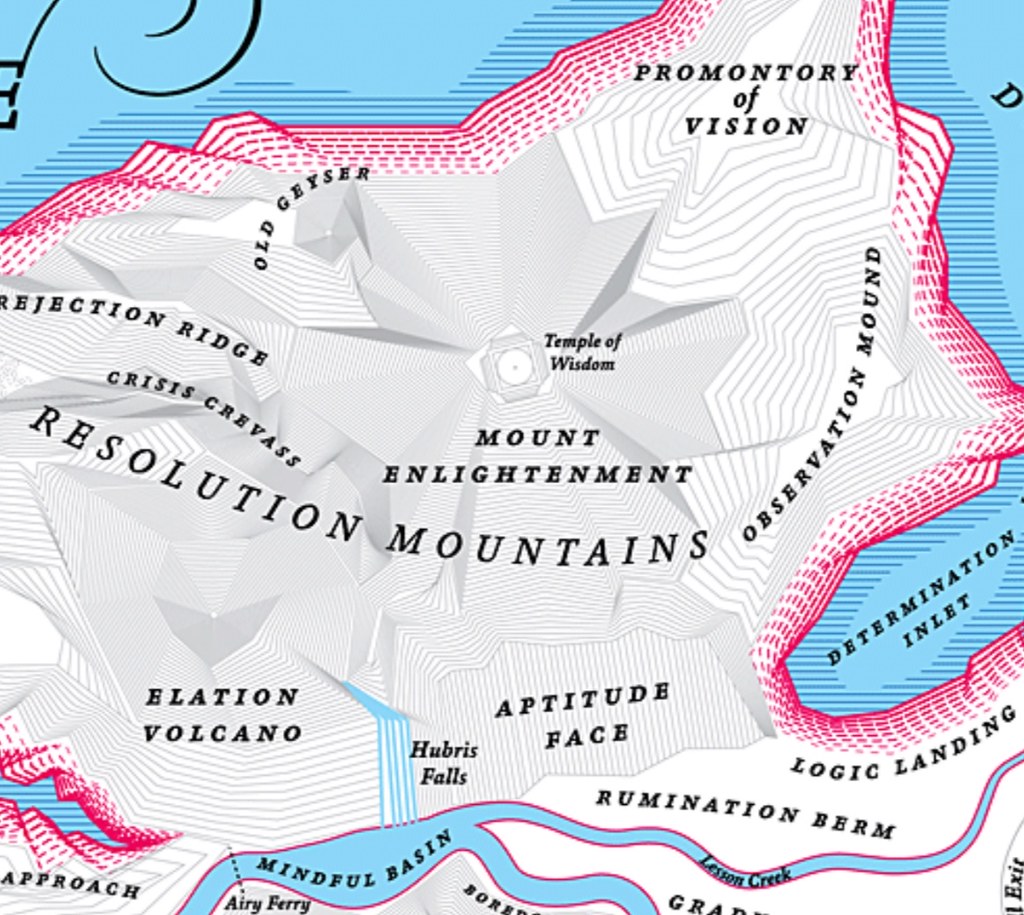

In addition to all these more utilitarian maps I’ve mentioned, I’m fascinated by all kinds of other maps: historical maps, Civil War maps, maps of fantasy and science fiction kingdoms, and maps of the mind (see the book of that title by Charles Hampden-Turner). It is one of my oldest books purchased more than 40 years. A book that survives that many moves is quite an influential part of my library. Another good book on historical maps is “The History of America in 100 Maps.”

Its a real shame we’re losing the ancient art of map reading to newer technologies such as GPS and Google Maps. But just like printed books are still

selling well and ebooks may never supplant them, so too will printed maps be around for some time to come. I just trust them more than listening to some robotic voice tell me when and where to turn. In a large city with its intricate maze of streets that may be a good option. But for traveling along “blue highways,” I’ll take an old-fashioned map any day.

Map of my third solo trip by car around the country, 1986-87

South Carolina highway road maps, 1959 and 2009

South Carolina Atlas and Gazeteer

Detail of a Forest Service map of the mountains of North Carolina

A portion of the South Carolina Atlas and Gazeteer showing back roads I am very familiar with

Detail of a map of Nebraska showing two recommended day-trip travel routes, one of which I will never forget. Such an amazing vast and beautiful part of the country, and relatively unknown.

Portion of the map of the fantasy land of Norman Juster’s book “The Phantom Tollbooth”

“America from the Road,” the book that started it all for me as I planned my first round the country trip. 1984

Last updated June 25, 2020

Loading comments...