On Hayabusa, Hayabusa 2, and the people who would do such things in The Amalgamated Aggromulator

- Sept. 23, 2018, 5:01 p.m.

- |

- Public

Hayabusa is the Japanese word for peregrine falcon.

There is a lovely, sweet movie - I had to order the DVD from Japan - about the probe named Hayabusa.

Hayabusa was the first probe to return particles from an asteroid to Earth for study. It was a great achievement for Japan.

It had all kinds of problems. A solar storm knocked out some of its solar panels en route, restricting what could be done during the mission. It lost two of its reaction wheels it used to maintain orientation and had to use thrusters (jets that expel gas) to compensate. It suffered computer problems at crucial moments. The transmitted command from Earth to release its tiny mini-lander MINERVA arrived at a moment when Hayabusa happened to be rising to maintain altitude over the asteroid, so the lander flew away into space. There was a long, uneasy loss of communication during its return to Earth. People thought it might have been lost.

Yes, I have just become aware that I am actually typing an ad for the movie mentioned above and, yes, you should arrange to get hold of it. Why not? Hold a showing. As they leave, people will look at you funny.

But really I want to say that space is hard and that long-range space probes are long, long, lonely, hopeful bets with trouble and with chance. Bets of care and brain against all that.

Hayabusa was launched in 2003. It made rendezvous with the asteroid Itokawa in 2005. Its re-entry capsule came down in South Australia in 2010.

The same solar storm that took out the solar panels, or other storms, may have been responsible for the failure of Hayabusa’s reaction wheels. Reaction wheels have been failing impressively all over the place for years - the space telescope Kepler’s wheels, for example - with earthbound engineers figuring out clever workarounds to continue to get results out of their ailing craft anyway. Now, with analysis of timing of failures versus solar activity, there is a strong suspicion that solar storms may have been responsible, causing arcing across the gaps between the housings and the ball bearings, creating pitting and burrs. New reaction wheels are increasingly made with ceramic bearings, so the problem may have been on its way out even if this theory had continued to escape us. But the thing is, nobody knew.

If a potential problem is figured out while your probe is still on its way . . . well, you’ve already sent the probe. The lander Cannae that dropped from the spacecraft Rosetta was supposed to fire harpoons to make sure it didn’t just bounce off Comet 67P, but the harpoons failed to fire. The harpoons were supposed to be propelled by exploding nitrocellulose. This happened in 2014. But a test by a Danish aerospace concern had already found that nitrocellulose didn’t explode as expected in vacuum - in 2013. And it didn’t matter, because Rosetta had been launched all the way back in 2004.

All you can do is learn from past mistakes, build as well as you can, persuade the people who control the funding that your voyage of discovery is worth it - not necessarily in that order . . . and then make another long, slow, daring bet with the unknown.

People bet their whole careers on these long, slow gambles.

And now the Japanese space agency JAXA has Hayabusa’s successor, Hayabusa 2, out at an asteroid about the shape of a ten-sided D&D die, a little asteroid named Ryugu. Hayabusa 2 was launched in 2014 . . .

. . . and so far it appears that the Japanese engineers have learned their lessons very well indeed. :-)

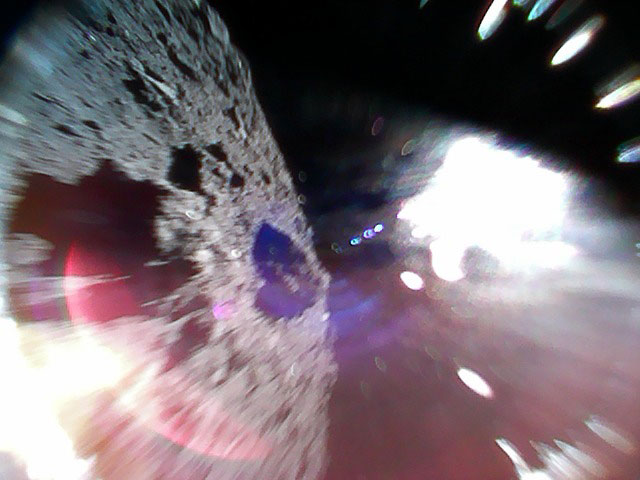

At this moment, two very small rovers are on Ryugu. Hayabusa 2 dropped them from 55 meters up two days ago. The rovers are 18 cm across and 7 cm tall. They look like little flat cylinders. They are little flat cylinders. They have no wheels. Wheels wouldn’t work on Ryugu; they’d only nudge themselves out of contact with the ground. When one of these rovers wants to hop, it spins up an internal flywheel and then, clang!, stops it cold, and this jolts the cylinder over - sending it sailing through space for maybe fifteen minutes to a new position many meters away.

Ryugu is a single kilometer across, or slightly less, and Ryugu’s equatorial surface gravity is 1/80th of Earth gravity. Escape velocity for Ryugu is thirty centimeters per second - about one kilometer per hour. The gravity is so low that . . . well, I’ve been puzzledly trying to find out whether Hayabusa 2, which has been keeping a distance of 20 km since its arrival in late June and will continue to do so between its approaches on different errands, is even in an orbit around Ryugu at all. I mean, you might as well; it’s a way to stay without using fuel. (Normally there’d be absolutely no question, because otherwise either you’re leaving or you’re landing.) But the gravity is so weak, the speed involved in an orbit so very slow, and the orbital stability so relatively minor compared to disrupting influences from far away, that I am tempted to take at face value the odd descriptions I keep seeing of Hayabusa 2 maintaining a “hovering distance”. Hayabusa uses an ion drive; it ionizes atoms of xenon and magnetically repels the atoms. An ion drive produces a very slow acceleration but can do so for very long periods before it uses up its propellant. The force it exerts is measured in millinewtons. But, with Ryugu, using an ion drive to hover might even make sense. I’m just reluctant to accept it because I’d think they’d want to conserve the xenon to use for velocity changes.

Hayabusa 2 will descend to Ryugu a few times over the next few months. It has yet another rover to drop, and also a slightly larger European-built lander. It will dip very, very close indeed to the asteroid - the first Hayabusa actually made a full landing, somewhat inadvertently - so it can shoot a projectile at the asteroid and then catch part of the resulting puff of debris. Then it will use a large copper impactor to make a brand new crater - and then it will descend again to shoot a projectile into the bottom of that new crater to collect samples of dust from there.

It is going to be attending Ryugu as a bumblebee attends a sunflower.

And what I want to remember to do here is try to capture just how and why attempts in space - and successes in space - lift my spirits so.

It’s because people spend themselves on such exacting technical tasks - and for the sake of pure curiosity, of sheer knowledge . . .

And because people are

trying

some

thing.

This against a backdrop of - well. You know. The most amazing rumpled hatefulness-tinged ingrown human foolery. Even the constructive things are obscured by it, turned into political games by it. Delayed decades by it. Everything subordinated by tides of inertia and billows of lack of interest. The accustomed colors. With a sprinkling of the special politicians . . . Well.

One can find inspiration in the work of scientists and technicians on Earth, yes. One can find them. One can pore through what they’re doing. And some of the things they’re working on on Earth are very important indeed. But - no, we’ll skip my speech about how important things relevant to those vital concerns may come from space too if we try, if we start filling in all the missing horseshoe nails. What I do want to say is that - in space - particularly well away from Earth - there’s no “game” yet, in the The Wire sense. There’s only pure knowledge, pure frontier, and the vast gulfs and the unknowns and the discovery and the great difficulties and the long, daring bets and the sheer dreaming human will. Even the most Earth-based parts where the ingenious devices are conceived and debated and researched and built; even when it’s a matter of the delivery systems themselves, of trying to get a new thing out of the atmosphere in the first place. That too.

And I’m failing to say it right, and I knew I would. I knew I wouldn’t get it.

But yes. In space, toward space, separate from all our bullshit, people are

doing

some

thing,

trying

some

thing.

Something new. Somewhere new.

People spend themselves. They bet themselves.

And sometimes they fail, and learn. And sometimes they succeed, and learn more. We learn.

And that’s human beings doing that, being that.

And it is beautiful.

(Yes, I know the thing to do would have been to extend this to a final section about what it was like seeing New Horizons’ pictures of Pluto and where the hell are the craters?!?, but the fact is I’m tired. You remember. Fill that in yourself.) :-)

Last updated June 08, 2020

Loading comments...